|

Power boats rip down Lake Chelan's 50-mile spine, churning the glimmering blue water white. The roar of the motors shoots into the surrounding hillsides dotted with homes modest and massive, old and new.

One in particular mixes an old idea with new style.

High above this watery playground smack in the center of Washington sits the

Glidehouse, a prefabricated -- or modular -- home designed with form, function and financing in mind. This prefab wonder, the brainchild of architect

Michelle Kaufmann of San Francisco, introduces a new generation of modular houses.

Today's prefabricated house is a far cry from the flimsy, sterile manufactured housing of yesterday and considerably different from the modular faux tudors and colonials built by large modular- and kit-house manufacturers. These architect-designed prefabs capture a clean, modernistic aesthetic and sport airtight construction, sustainable materials and affordable price tags.

Andrew and Kindra Reid of Kirkland, Wash., just call it their new vacation home.

Initially, the couple bought it as an investment. Andrew knew of the Glidehouse through his work at a mortgage company offering to finance it. The Reids planned to truck it from Menlo Park, Calif., where it was on display last spring at Sunset Magazine to celebrate its innovative design, to Chelan and sell it.

"Once we saw the house with all the windows and the bamboo floors, we thought 'This is ours. This is our space,' " says Kindra, who never associated modern design with warmth, light and comfort. "I always thought of modern as stainless steel from floor to ceiling and not a lot of color. The Glidehouse is the antithesis with its caramel floors and wall of windows."

Named in part for the wall of sliding wood panels that hide the house's storage spaces, the Glidehouse borrows the best features from other architectural styles and packages it under one roof. It pulls the outside in through unadorned windows and sliding doors, like a midcentury ranch house. Its rectangular shape, angled roof and walls of glass echo the International Style of architecture made famous by Le Corbusier and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and brought to the masses by the likes of Joseph Eichler and Frank Lloyd Wright's Usonian design.

Today, the sleek profile of the one-story Glidehouse crouches on the rugged hillside above Lake Chelan on a spot that took five sticks of dynamite to flatten. The house sits parallel to the lake's shoreline, its front door faces uphill, and the glass-walled backside opens to the dramatic landscape below.

Despite the house's open feel, the Reids had some initial reservations. How was 6-foot, 4-inch Andrew going to feel living in a house designed on a 14-foot-wide floor plan?

"We were a bit worried," Kindra says. Was it substantial enough? Will we feel caged?" Turns out their worries were unnecessary.

Kaufmann's design revolves around two 14-by-48-foot mods -- or units -- joined at the side. One houses the living/dining/kitchen areas, while the second holds bedrooms and bathrooms. Additional mods can be attached in a variety of configurations. Knowing they'd be entertaining, the Reids added a third bedroom/bathroom mod, bringing the square footage to 1,600. Although the base price for a Glidehouse begins at $120 per square foot (excluding land and site preparation), the Reids popped up to about $210 a square foot, Kindra explains, because of upgrades in materials and appliances.

Near-instant gratification is one of the benefits of modular housing. It can be pieced together in half the time it takes to build with traditional methods on-site, says Timi Starkweather of

CRG, the Redmond, Wash., firm that turned Kaufmann's blueprint into reality. Built to the same code required of any home, Starkweather says her modularly built homes "exceed the standards. . . . We have to build these to move on a flatbed and be hoisted by a crane if need be," she says. "They are built in an enclosed environment -- no shrink or pop. . . . There's no waste. It's a beautiful product."

Reid, who watched her in-laws build a conventional home on Lake Washington, was struck by two contrasts of constructing a modular home in an enclosed factory. One, there's no stopping because of bad weather. And two, modular construction produces less waste and leaves a lighter impact at the home site.

Modular, manufactured and kit houses tend to get clumped together when talk turns to options other than traditional on-site construction. And, indeed, for years, none stood apart.

What sets today's modular homes above others is an affordable yet stylish design more apt to turn the head of your hip nephew living in The Pearl than, say, your aunt from Raleigh Hills.

From Finland to Oregon, architects are rethinking prefab using cargo containers, steel structures, sustainable materials, efficient heating and cooling, and computer-aided design.

Clearly, it's catching on.

With names such as Dwell Home, LV Home and Little House, prefab design has made its way to both Target, via Michael Graves' room additions, and Canadian manufactured housing giant Royal Homes, which has unveiled an architect-designed modern line called Royal Q Home.

Influenced by both the spare Japanese aesthetic and the works of Eichler and Charles Eames, Kaufmann, who spent five years as an associate with Frank O. Gehry + Associates, set out to design a modern, sustainably built, affordable house. She apparently hit a nerve. After the Glidehouse debut last spring, more than 400 people signed up as potential buyers. There are currently more than 30 Glidehouses in the works.

That level of interest doesn't surprise Portland architect Fredrick H. Zal, of Atelier Z, nor does the initial skepticism that prefab generally receives, since some of the bad rep is justified -- think mobile home, he says.

"But, think about the sprawling suburban lots," he says, pointing to the sea of sameness of many developments. Some of these on-site, stick-built homes look like they came off an assembly line, with little distinction between them. If they really were prefabricated, Zal says, owners would have saved enough money on construction to customize everything from the exteriors to how the house sits on the land.

Zal and others cite the way cars are made to explain prefabrication, or mass customization, as Zal likes to call it. Cars come from an assembly line, but each one can be built to order for color, wheels, suspension system, upholstery, you name it.

"As designers of prefabricated homes, it is not our goal to create hundreds of repetitive, indistinct homes," Zal says. "It is our goal to create homes that may be customized for the needs of individual families and their neighborhoods."

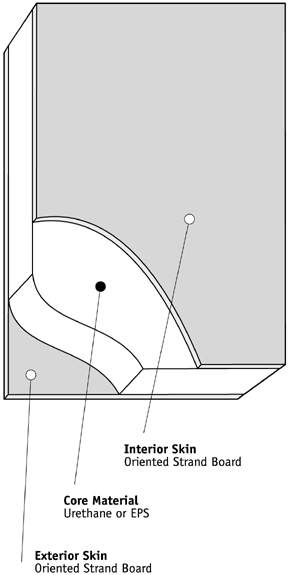

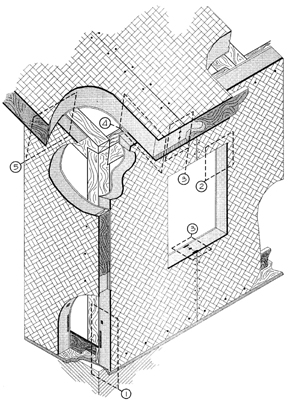

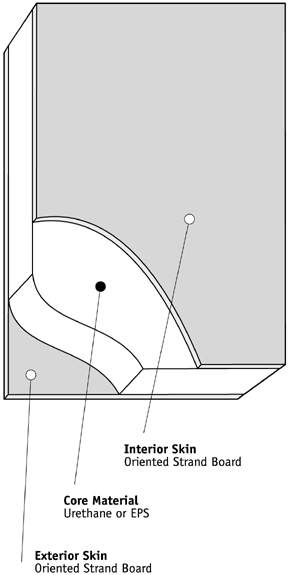

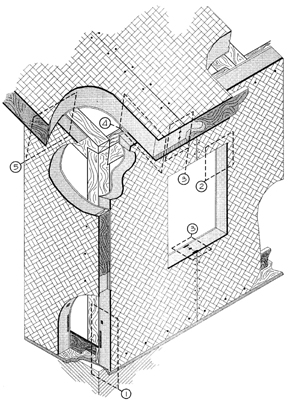

Zal's currently working with a homeowner to remodel a turn-of-the century Portland house to open it up, and add room and height. To help keep within the owner's "minuscule" budget, Zal uses premade walls, also known as prefabricated structurally insulated panels, wherever he can.

"Prefab will eventually get to the point where people will know more about prefabricated technology and understand how it pays off," he says.

Kaufmann couldn't agree more.

"The interesting thing is that technology is developing, but it's more about sharing of information and changing the misconception of prefab."

Between developers who push for site-built homes to maximize profits, to the public lumping modular and manufactured housing in the same category, it's no wonder everyone's confused, she says. But once people realize prefab's benefits, the layers of misconception peel away.

Where possible, Kaufmann used renewable materials, such as bamboo flooring; recycled materials, such as counters made from paper and fly ash; and energy-efficient appliances and toilets. She also placed clerestory windows on one wall and glass sliding doors on the opposite for cross ventilation to reduce the need for air conditioning.

"The economy of prefabrication is not the only benefit. It holds out the promise of an affordable dream home," says Allison Arieff, editor in chief of Dwell magazine and author of "Prefab," (Gibbs Smith Publishers, 2002) now in its fourth printing.

"There's tons of new home construction," Arieff says. "But are they good or what we want to live in? For $200,000, you're not going to have your pick of homes, and in various parts of the U.S., you'll have to make compromises."

Last year a Dwell magazine contest asked architects to come up with a $200,000 prefabricated house that, according to the magazine, "bucks the status quo and embraces all the benefits -- aesthetic, environmental, economic, technologic -- that prefab construction has to offer."

Interest in the winner has been immediate and intense, Arieff says. She thinks she knows why.

"The houses we live in today are not too different from a century ago," she says. "It's baffling to me."

Perhaps prefab will spawn a new, more discriminating home buyer. In the meantime, Kaufmann's still waiting for her own Glidehouse to be completed.

Kaufmann's husband, Kevin Cullen, took her original simple, modern, green design and started building it like a traditional home, rather than having it manufactured and trucked in. He launched into construction before Kaufmann found a manufacturer to mass-produce the house.

"We're still building our Glidehouse, and it's identical to the one that was in Menlo Park," Kaufmann says. "And it costs us 50 to 60 percent more. . . . We're in the frustrating-yet-unique position to assess site vs. prefab."

And Kaufmann has come to a simple conclusion: Prefab is the way to go.

"It is so much better, let me tell you."

|

|

SIPs:

Structural

Insulated Panel System

images

courtesy of:

|