|

Weighing 5,500 pounds, faced in marble with its edges clad in stainless steel, the door between Michael and Pat Del Castello's Pearl District living room and personal art gallery feels like the entry to a science-fiction movie.

It required more than 40 meetings between architect, engineer and builder to design and build. A sag of 1/16 inch would mean a scratch in the floor.

"If there's ever an earthquake," says its designer, Jeff Lamb, "this doorway is where you want to stand."

Looking past the question of why anyone might want a door like this, much less need one, it is a marvel of engineering and craftsmanship. Yet it is merely one among dozens of similar flights of fancy - or folly - to be found in the Del

Castellos' new Portland pied-a-terre.

Founder of the nation's largest vacuum-parts manufacturer and a wheeling, dealing collector of everything from Popeye memorabilia to Wells Fargo stagecoaches, Michael Del Castello, 56, is a wealthy man who loves wealthy ways. "Playing for me is buying," he quips.

A tip from Twist's Paul Schneider led to Lamb. Designer of the faux-domed 1000 Broadway Building and the steel, glass and plaster interior puzzle of the American Institute of Architects headquarters, Lamb has a reputation for big ideas, endless energy and little discipline - the closest Portland version of a "bad-boy designer" up to Del Costello's brand of excess.

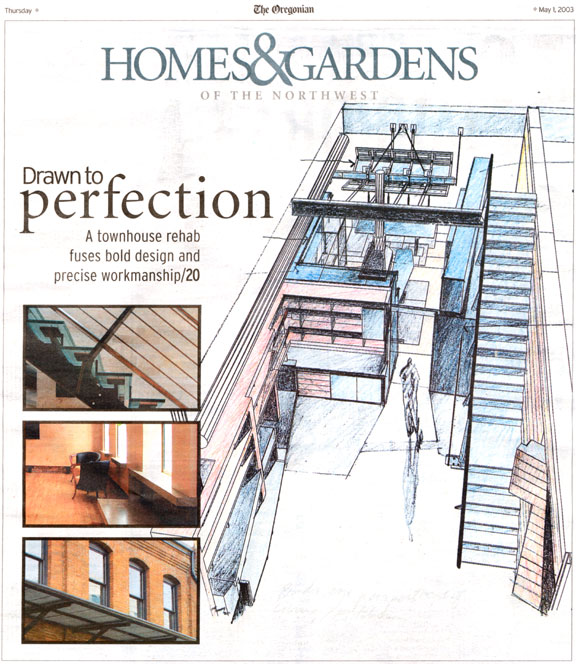

The result is 3,600 square feet of custom space that some visitors will find cool and others appalling. But whether one likes it or not, Lamb's intense focus on every detail and Del Castello's ability and will to buy the best has resulted in a breathtaking series of examples of workmanship by the city's top fabricators.

"It's all from scratch," the townhouse's contractor, Don Tankersley, says of the one-revolution-per-minute motor transmission driving the marble door. But it's a phrase that applies to virtually every square inch of the

townhome. "I mean, who builds a vault-door transmission?"

A chronology of the project offers a little understanding. On a Portland visit to see his daughters three years ago, Del Castello spotted the six historic North Bank Depot Building townhouses under renovation on a drive through the Pearl. He optioned all of them. After one architect failed to satisfy the avid collector's urge to "live in a museum with all my toys," Del Castello hired Lamb - giving him three days to come up with a scheme.

Five days later, the architect showed his stuff and got the job. Del Castello ultimately scaled back to only two of the six units. ("Too many doors," he says. "Which one do I go in?") But he and Lamb stuck with the design, cramming much of the plan for the original 12,000 square feet into the current 3,600.

"Jeff's ideas were my ideas, but I just couldn't get them out," Del Castello says. "We both have tremendous egos, but we both appreciate when one of us takes the other's idea another step. We had lots of great dinners and lots of wine, and most of the design developed in restaurants. We never stopped talking about this project. It was our life."

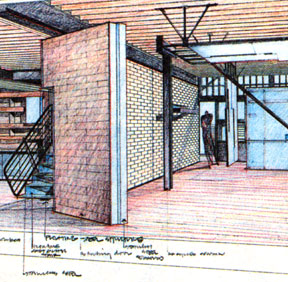

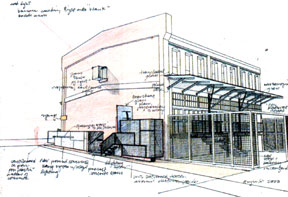

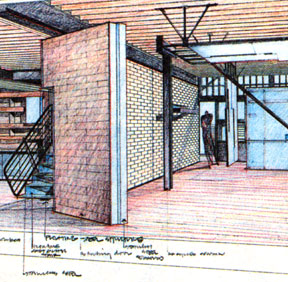

Lamb describes the design as "an intervention into the building's history." He aspires to the mix of modernity and history in Italian master Carlo Scarpa's work, such as his famed renovation of the Castelvecchio Museum in Verona. "You respect what's good," he says of what was essentially an early century train-car storage dock.

Inserting the new elements into the shell of the old, Lamb used only steel, glass, marble, concrete and wood. No material touches another without an interface - most often blued steel, similar to that found in guns, one of Del Costello's many collecting interests.

"No goop, no caulking, no trim," Lamb says in a sharp staccato. "Everything is what it is."

Del Castello's company makes vacuum components for high-tech clean rooms and laboratories. Lamb strove to design the townhouse with a similar feel of finely machined appliance.

"Each element in his home is its own piece of art," Lamb says. "There is no back of house. There isn't anything you can't look at."

The ceiling, for instance, Lamb describes as a "silver cloud" of steel mesh masking sprinklers, lights, speakers and ventilation. The walls and window surrounds are often puzzled together from sheets of maple plywood hung on a steel frame and punctured with niches for Pat Del Castello's Murano glass collection. Ninety-four separate lighting circuits allow every square inch to be tuned for any given mood. The floors are salvaged from an old Boston barn. Counters are concrete, smoothed to a soap-like finish and knife-like edge. Each door is stainless steel or glass. The "everything-is-what-it-is" aesthetic goes right down to the gas fireplace, where the flames dance not over ceramic wood, but black river stones.

"Some say it's too much," says contractor Tankersley, who has built equally excessive interiors for such clients as

Cole-Haan design chief Gordon Thompson, along with the local style landmark, Bluehour restaurant. "But there's not a superfluous rivet in it. I think it'll stand the test of time."

Custom fabricator Tom Ghilarducci says he has spent 24 hours a week for the past two years on the townhouse. Among his tasks was hand-treating all the exposed steel. And a lot of steel there is, from the frame seismically reinforcing the masonry walls to the custom-extruded baseboards Lamb designed. Ghilarducci sandblasted every square inch, then spritzed with acid, wiped with water and finally clear-coated for the gunmetal-blue finish.

"It's exhilarating to work on something like this," Ghilarducci says, "And it's exasperating."

Del Costello estimates he paid around $450,000 in design fees, which for Tankersley adds up to 170 pages of detail drawings. Del Costello declined to say what the cost of the remodel totaled for the $887,000 pair of townhouses he ultimately bought. But whispered estimates run $2.5 million to $3 million.

Yet Tankersley says Del Costello required careful explanations for every $50 receipt.

"It's not about the money to Michael," Tankersley says. "It's about the value."

Push a button on any one of the 10 stainless-steel-framed sliding glass doors and, like a switchblade, out pops a door pull shaped like a pistol trigger guard, designed by Lamb with machinist Fergus

Kinnell. Eleven-foot-long, cast-glass tops fold over bar counters like watches in a Dali painting, each fabricated by artisan George

Batho. The master bed's headboard is built like a skyscraper, an interior frame holding panels of ebony and cast glass for a seamless exterior. The master bath's shower is cylindrical, the rounded glass custom-built by Portland's Benson Industries and fitted into a rolled stainless-steel bar made by Kinnell working with a company that once fabricated components for dams.

Lamb notes that, as a manufacturer, Del Costello deals in parts with zero tolerances. As a collector of everything from Ferraris to rare guns, he cherishes craftsmanship.

"In all my projects, there's the value-engineering phase where the fluff gets cut out," Batho says. "Well, on this, the fluff never got cut out."

An average custom interior project might have two or three key custom glass pieces, he adds. Del Castello had 27, and most of them, because of Lamb's design changes, got made three times.

"Jeff standing in that loft giving a tour," Batho observes, "is like watching him stand in his own head."

But like the old water-glass metaphor, the finished townhouse seems lost as to whether it is a trainyard bank building half full of a well-designed, contemporary update or a desperate attempt at high style half-emptied of its shell's rich historic patina. In short, the North Bank Depot Building doth runneth over with Lamb's design.

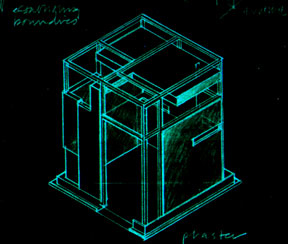

Barely standing in relief from all the details is the architecture: the three key, space-defining features of the marble wall and its hefty door, what is officially Portland's first legally approved glass stairway and what Lamb calls "The Cube," a bathroom.

Del Castello intends half of the ground floor to be a gallery for his collections, which he plans to open First Thursdays. The marble wall and vault door dramatically separate gallery from living space.

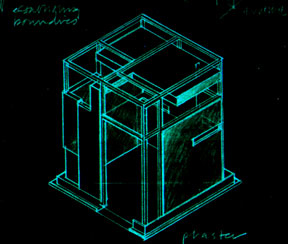

By code, retail spaces must have a wheelchair-accessible bathroom. With no easy place to locate it, Lamb says, he simply decided to turn the bathroom into a work of art itself, a poured-concrete box cut with inserts of semi-translucent glass, all turned at an angle to the room to emphasize its

"objectness." Knowing that concrete walls amplify sounds, intended or not, Lamb equipped The Cube's interior with a rushing water fountain that automatically commences when the door shuts.

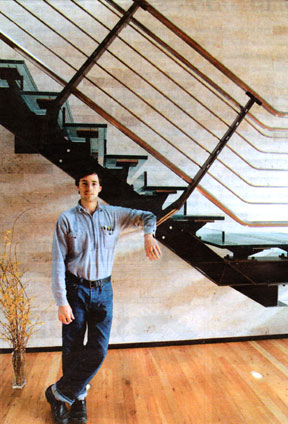

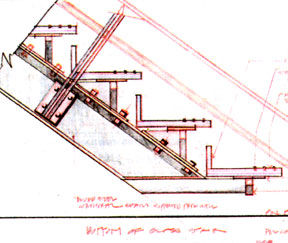

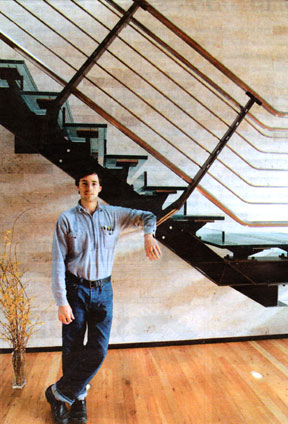

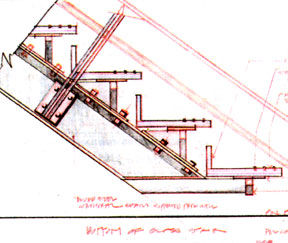

On the private side of the marble wall, the glass staircase rises to the loft. With its steel frame pivoting from the wall in an ode to the similarly floating stair in Mexican architect Luis Barragan's house, the ethereality is further lifted by the glass treads fabricated by Benson Industries on a frame beautifully welded by Ghilarducci. The top of three layers of clear, laminated glass is slotted and fitted with 1/4-inch strips of stainless steel to prevent Del Costello from slipping in his favored footwear - cowboy boots.

Any of these three features alone could be the centerpiece of a pretty fine townhouse conversion, with the three together making a powerful statement of both style and wealth. But like many collectors, Del Castello is as interested in volume as singularity. "He's a true patron of the arts," says Mark Newman, whose handiwork surrounds the space in the wood-panel walls, the aluminum-mesh ceilings and every piece of wood cabinetry. "It's all just another piece in his collection."

Though Del Castello boasts that he has sold every one of his other collections for a profit - from his first of coins to more recent ones like the Ferraris - he concedes that turning over the townhouse he calls "my little box of toys" may be tough.

"It's definitely overbuilt for the area," he says. "But there's a lot of money out there. Somebody just might say, 'Hey, that's pretty special. I want to own it a while.' Maybe a lawyer. It could be a great law office."

Meantime, he's planning a plaque that will read:

"This building is known as the North Bank Depot Building West Wing. Built in 1908, it was used as a freight warehouse by the railroad. The brick layers would be proud of the transformation it's undergone The vision was to show the original skeleton of the building. The interior was to be glass, concrete and stainless steel. . . . Our goal was perfection. This has been achieved."

Randy Gragg: 503-221-8575;

randygragg@news.oregonian.com

Photographs:

Serge A. McCabe, the Oregonian

Rendering:

Jeffrey D. Lamb

Drawings:

Fredrick H. Zal + Kimberley A. Shiell |

"Michael

builds connections between things you never see: gaskets, clean rooms,

vacuum systems. Working with him has been fascinating. Now

the first thing I ask about anything I'm designing is, can I

manufacturer it?" -Jeff Lamb, architect, on owner Michael Del

Castello.

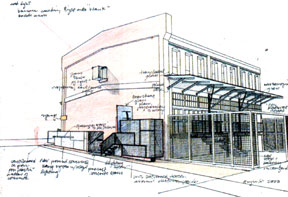

Working

closely with the State Historic Preservation Office, Lamb crafted the

exterior of the historic building to contrast new with old.

Architect

Jeff Lamb's desire to make every new component in the townhouse "an

insert" led to the design of "The Cube," an elaborate

concrete/glass/steel bathroom complete with cascading water.

Lamb's

design with Mark Newman's craftsmanship turns walls, shelves and the bed

he sits on into a tapestry of exotic woods, among them mahogany, ebony

and rosewood.

"There

isn't a thing in the whole project that wasn't a stretch. What

made it different is the puzzle-like way in which every piece comes

together. The beauty is in the synthesis." -Mark Newman,

finish carpenter

The

vault-like door Fergus Kinnell built between the gallery and living

quarters keeps public and private decidedly apart and, with the slow

opening and closing, ritualistically entered.

"I

see myself as a finish carpenter working in stainless steel."

-Fergus Kinnell, steel fabricator

"An

average project maybe has one or two or three custom pieces. With

this, there were 27 pieces and all of them were made three times."

-George Batho, glass artisan

"Some

say it's too much. But it all has a purpose. I've lived here

for two years, and I've fallen in love. There's not a superfluous

rivet in it." -Don Tankersley, contractor

Steel

fabricator and furniture designer Tom Ghilarducci worked with Benson

Industries, a locally based rising national star in glass fabrication,

to realize Lamb's design for Portland's first code-approved glass

stairway.

"It

is just a residential buidling, but it's built as though it were for a

government. It's an ode to craftsmanship. It took two days

to one panel because it just did." -Tom Ghilarducci, steel

fabricator |